Lessons of a vaccine “strollout”

What would be an article about vaccinations in the COVID-19 pandemic without using the word of the year? That’s right, strollout. Essentially this word speaks specifically to the role that the Federal Government played delivering a slower than needed vaccination program in Australia.

Throwback to the vaccine strollout

The Federal Government passed up the opportunity to secure sufficient vaccine supply at the outset, turning down available vaccines from international suppliers so that they could work on local production that is yet to come to fruition. Moderna, for example, arrived on our shores almost a year after it was approved for use in the US. We had no existing capability for vaccine production, and it was known that it would take a while to establish this, but the Feds thought we had plenty of time. Which we did, until we didn’t. Once the delta outbreak kicked off in June 2021 we were in a scramble to secure vaccine supply.

The Federal Government, in particular the Prime Minister, were fixated on a metaphorical arm wrestle with the state governments about who should be delivering the vaccine program. A fine example of politics around a community need at a time when the community needed it most. Whilst I can’t stand the word strollout, I think it reflects more than just a cleverly placed ‘word’ in a well-timed tweet.

Lesson 1: the Federal Government are not best placed to deliver a vaccination program. States have always done the lion’s share of health service delivery

Crisis inspires action

During the 2020 wave of the pandemic we lived in lockdowns and watched the news on the international situation. Our borders were shut and we relished the protection our island home gave us from the impacts of COVID-19. Whilst we watched countries such as Italy, the US and UK struggling against caseloads and death rates, our figures were low (in both rates and numbers) and we were happy that our public health advice was keeping us safe. We were apathetic towards COVID-19 vaccines because they were new, we were keen to see if there were any significant impacts to overseas recipients, and just frankly we didn’t feel that we needed them.

Fast forward to 16 June 2021 when one limousine driver was recorded as infected with the delta variant of COVID-19. This variant was the one we’d seen internationally spread with speed and impacts to health that we’d not yet seen during the pandemic. The confidence in our public health orders, and the apathy driven from a fairly successful 2020 response, meant that we were slow to restrict movement for anyone who wasn’t in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney. Before we knew it our whole state was in lockdown, with Greater Sydney’s lockdown lasting for nearly four months.

The public health response to the pandemic had utilised many levers, and before this time we had navigated the pandemic response effectively without much reliance on the need for a vaccine. This time it was different with super spreader events taking the delta strain into communities and households in ways we’d never seen before. Of particular concern were the outbreaks in South Western Sydney, communities that provided the workforce that kept our restricted economy moving through transport, logistics and essential frontline staff. It became time to pull the lever on vaccinations, and from 3 July 2021 our governments began reporting daily vaccination numbers (see above image). The Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) became one of Australia’s best known and frequently used data sources. With limited vaccines available, the NSW Government and the National Cabinet began relocating vaccine to areas of concern. I could just imagine the war room. MPs using one of those big sticks to move little vaccine vials across the LGA’s across the country where they needed vaccine urgently to support a growing outbreak.

Lesson 2: Vaccine hesitancy is not a thing. It was lack of supply and access barriers that was driving our low vaccine supplies. People want to be empowered to take care of their own health.

Our community is broad- it’s not just the mainstream

Campaigns to drive community action are a fairly simple equation. We need to get to result X, so to achieve that we need Y people to take Z action. To achieve this a project plan is set out that is based on a budget, a timeline, and a scope. Often there are trade-offs, or considerations, that mean that due to budget limitations your timeline is shortened or the number of people you engage are reduced. What this actually means is that usually a community campaign focuses on the 80% of mainstream, middle class, English speaking community members. The result is usually achieved, so that means the formula is right, right? Wrong.

What we saw during the delta outbreak was that COVID was disproportionately impacting the diverse community groups. It was spreading in ways that we hadn’t seen before. There was a funeral in South West Sydney and on a cultural level attendance was more important than the public health orders or risk of disease. There was the outbreak in Western NSW that ran rampant through the Aboriginal communities in places such as Wilcannia. Despite the prioritisation of Aboriginal people in the initial strollout, the lack of vaccine supply and the inability to access it through their trusted health services meant these community members simply hadn’t received their vaccines.

Disproportionate impacts require a disproportionate response. Although this isn’t always the mantra adopted in a campaign, it was clear that this year was the time to change things. NSW Government were allocating resources and efforts to connect with multi-cultural and diverse groups, breaking messages into language and delivering vaccines through local, trusted places such as Mosques and Aboriginal Medical Services. NSW Police activated their multicultural team to support communities in their time of need during lockdowns, but also to assist and enable them to access vaccines. After seeing that targeting specific groups actually played out as alienating, the approach shifted to promoting the myriad of individuals, races, religions in our communities. Locally based community services became a key stakeholder as they had the relationship and access to engage their clients who hadn’t traditionally been the target of a mainstream campaign. In the Illawarra, the Vax the Illawarra campaign utilised volunteer effort and ambassadors to tap into First Nations, ethno-specific, LGBTQI+, religious, education, disability and business communities, and they are of all ages and genders.

The quick-fire response to getting vaccinated, once we tapped into the drivers for the many subsets of our broader communities, show that once people are engaged on a personal level they are enabled to participate in a community response.

Lesson 3: Our community is a rich and beautiful tapestry of different groups who all need to be involved, engaged and empowered to drive effective community-wide change.

The ultimate lesson

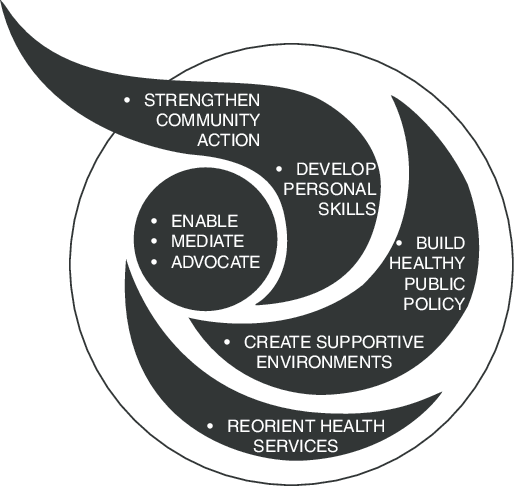

The overarching lesson from this pandemic is that we have successfully engaged consumers to strengthen community action in ways different to any campaign before. Personal skills were developed through targeted vaccine literacy campaigns. We have utilised supportive environments and re-oriented health services so that services outside of the traditional health ecosystem have been engaged in service delivery. The result is we have successfully achieved the mass scale vaccination rates we were hoping for. Sometimes it’s important to listen to and work with the community, so that they can help us shape a program that is truly successful.

-written by Toby Dawson (Head of Strategic Partnership, IRT)